Manute Bol, a towering Dinka tribesman who left southern Sudan to become one of the best shot-blockers in the history of American basketball, then returned to his homeland to try to heal the wounds of a long, bloody civil war, died Saturday at the University of Virginia Medical Center in Charlottesville, according to Sally Jones, a spokeswoman for the hospital. He was 47 and lived in Olathe, Kan.

The cause was severe kidney troubles and complications of a rare skin disorder known as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, said Tom Prichard, who runs Sudan Sunrise, a foundation that is building a school near Bol’s birthplace in Turalei. Bol had been hospitalized since late May when he fell ill during a layover on a trip home from Sudan, Mr. Prichard said.

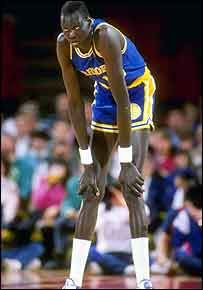

Though he wore size 16 ½ sneakers and had a pair of the spindliest legs ever to protrude from a pair of nylon shorts, Bol, at 7-foot-6, was an athletic marvel. He arrived in the National Basketball Association in 1985 and promptly set a rookie record by blocking an average of five shots per game — a total of 397 for the season. He is 14th on the N.B.A.’s career list with 2,086.

Fans flocked to see him and roundly urged him to shoot whenever he touched the ball. Despite being able to reach above the 10-foot rims flat-footed, Bol was not a scorer. He averaged fewer than 4 points a game in every season he played.

It was his defensive prowess, swatting shots away from the basket and discouraging opponents from trying to drive the ball past him, that kept Bol in the league for 10 seasons. The Washington Bullets drafted him three years after he immigrated to the United States in 1982, and he eventually played for three other teams: the Golden State Warriors, the Philadelphia 76ers and the Miami Heat.

For most of his career, Bol held the distinction of being the tallest player ever to compete in the N.B.A. But in 1993, the Bullets drafted Gheorghe Muresan, a Romanian who at 7-7 was a few centimeters taller than Bol. The Bullets brought Bol back to Washington to help teach Muresan how to play the professional game, but it took Muresan four seasons to compile as many blocks as Bol had as a rookie.

Bol eventually came to terms with the fascination Americans had with his height. When he was a young man in Sudan, he told The New York Times in a 1985 interview, his size was not so remarkable.

“My mother was 6 feet 10, my father 6 feet 8 and my sister is 6 feet 8,” he said. “And my great-grandfather was even taller — 7 feet 10.”

As a boy, Bol had tended his family’s cattle. According to a tale he was often asked to repeat in interviews, he once killed a lion with a spear while he was working as a cowherd.

In a 2001 interview with The Times in Khartoum, Bol said he dreamed of going back to Turalei and his roots. “I would have a big, big farm,” he said. “Then we have no worries about money. If you have the cows, you have the money.”

Bol returned to Sudan regularly during his playing days and once he retired, he became more politically active there. He went there late last year to check on the school construction, then stayed on to campaign for a candidate in the region’s presidential election that was held in late April, said Mr. Prichard, who had traveled there with Bol in November. During his extended visit, Bol became ill and was briefly hospitalized in Nairobi, Mr. Prichard said.

“He really felt that his country needed him,” Mr. Prichard said. “He really died for his country. He wanted to do everything he could to see southern Sudan make it through this election in the best possible way.”

Bol is survived by 10 children, including four with his second wife, Ajok, of Olathe, Kan., his nephew Mayom Majok said.

The cause was severe kidney troubles and complications of a rare skin disorder known as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, said Tom Prichard, who runs Sudan Sunrise, a foundation that is building a school near Bol’s birthplace in Turalei. Bol had been hospitalized since late May when he fell ill during a layover on a trip home from Sudan, Mr. Prichard said.

Though he wore size 16 ½ sneakers and had a pair of the spindliest legs ever to protrude from a pair of nylon shorts, Bol, at 7-foot-6, was an athletic marvel. He arrived in the National Basketball Association in 1985 and promptly set a rookie record by blocking an average of five shots per game — a total of 397 for the season. He is 14th on the N.B.A.’s career list with 2,086.

Fans flocked to see him and roundly urged him to shoot whenever he touched the ball. Despite being able to reach above the 10-foot rims flat-footed, Bol was not a scorer. He averaged fewer than 4 points a game in every season he played.

It was his defensive prowess, swatting shots away from the basket and discouraging opponents from trying to drive the ball past him, that kept Bol in the league for 10 seasons. The Washington Bullets drafted him three years after he immigrated to the United States in 1982, and he eventually played for three other teams: the Golden State Warriors, the Philadelphia 76ers and the Miami Heat.

For most of his career, Bol held the distinction of being the tallest player ever to compete in the N.B.A. But in 1993, the Bullets drafted Gheorghe Muresan, a Romanian who at 7-7 was a few centimeters taller than Bol. The Bullets brought Bol back to Washington to help teach Muresan how to play the professional game, but it took Muresan four seasons to compile as many blocks as Bol had as a rookie.

Bol eventually came to terms with the fascination Americans had with his height. When he was a young man in Sudan, he told The New York Times in a 1985 interview, his size was not so remarkable.

“My mother was 6 feet 10, my father 6 feet 8 and my sister is 6 feet 8,” he said. “And my great-grandfather was even taller — 7 feet 10.”

As a boy, Bol had tended his family’s cattle. According to a tale he was often asked to repeat in interviews, he once killed a lion with a spear while he was working as a cowherd.

In a 2001 interview with The Times in Khartoum, Bol said he dreamed of going back to Turalei and his roots. “I would have a big, big farm,” he said. “Then we have no worries about money. If you have the cows, you have the money.”

Bol returned to Sudan regularly during his playing days and once he retired, he became more politically active there. He went there late last year to check on the school construction, then stayed on to campaign for a candidate in the region’s presidential election that was held in late April, said Mr. Prichard, who had traveled there with Bol in November. During his extended visit, Bol became ill and was briefly hospitalized in Nairobi, Mr. Prichard said.

“He really felt that his country needed him,” Mr. Prichard said. “He really died for his country. He wanted to do everything he could to see southern Sudan make it through this election in the best possible way.”

Bol is survived by 10 children, including four with his second wife, Ajok, of Olathe, Kan., his nephew Mayom Majok said.